- Growth is falling, unemployment is rising, banks are being battered and people hounded for tax are killing themselves

- Something is up in India’s economy, if only the prime minister would admit it

Kunal Purohit 23 Nov, 2019

‘Tax terrorism’ is driving Indians to despair. Photo: AFPWhen Vodafone Chief executive Nick Read told reporters in London this month the company might have to shut up shop in India, the response from New Delhi was swift and unequivocal.

Almost as soon as Read had finished his press conference – in which he alluded to two lawsuits that have left the company owing US$55 million due to changes in spectrum licensing laws – media reports were relaying the Indian government’s “displeasure and disapproval” of Read’s “tone and tenor”.

Just 24 hours later, Read had apologised to the Indian government, blaming the media for misquoting him and claiming he remained “invested in India”.

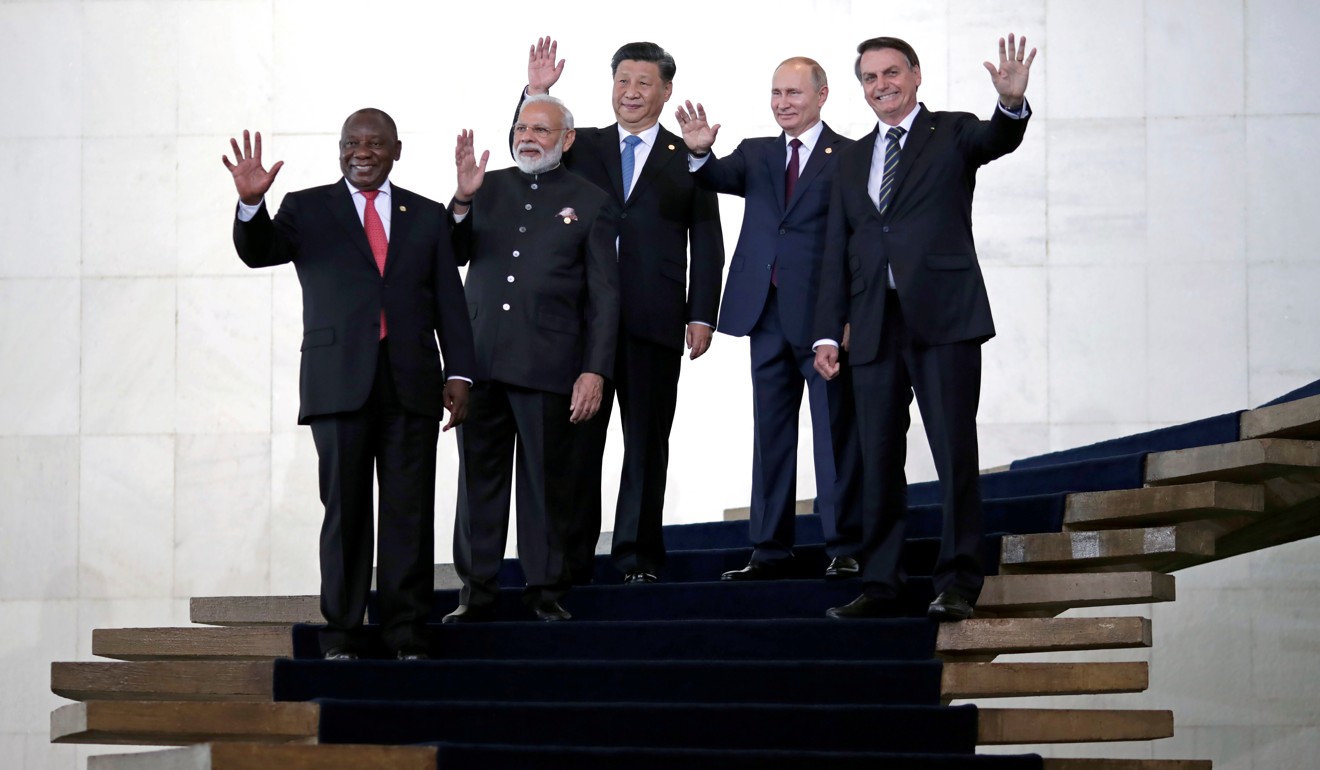

Ironically, as this was playing out, Prime Minister Narendra Modi was attending a summit of the developing BRICS economies in Brazil, where he touted India as the “world’s most open, investment-friendly economy”.

Narendra Modi with other leaders of the BRICS countries at a summit in Brasilia. Photo: Reuters

The two episodes, say critics, illustrate either myopia or outright denial on New Delhi’s part over the economic challenges headed its way. Just as danger signs are emerging in its economy – with early forecasts suggesting growth in the second quarter may have been as low as 4.2 per cent, the lowest since 2012 – many are wondering if the government’s attitude towards the business sector is making matters worse.

China, Gandhi or RSS? The real reason India snubbed RCEP trade pact

This week, former prime minister Manmohan Singh, a Cambridge-educated economist, wrote in The Hindu newspaper that “a climate of fear and mistrust” was impeding economic growth.

“Many industrialists tell me that they live in fear of harassment by government authorities. Bankers are reluctant to make new loans, for fear of retribution. Entrepreneurs are hesitant to put up fresh projects … Technology start-ups, an important new engine of economic growth and jobs, seem to live under a shadow of constant surveillance and deep suspicion. Policymakers in government and other institutions are scared to speak the truth or engage in intellectually honest policy discussions.”

India’s former prime minister Manmohan Singh. Photo: Reuters

RED FLAGS, ALL AROUND

Singh’s concerns about the economy are reflected not only in falling GDP growth. Rural consumption has plummeted by 8.8 per cent, the sharpest drop in more than four decades, while in manufacturing – one of India’s largest employers – growth is flatlining and was just 0.6 per cent last quarter.

Most global ratings agencies have downgraded their predictions for India’s growth in the next two quarters to less than 5 per cent. Such a figure might be enviable to some countries, but in India it is a cause for concern. The country’s annual GDP growth rate has averaged above 6 per cent for the past 70 years and hit an all-time high of more than 11 per cent in the first quarter of 2010.

With many companies turning to cost-cutting measures, the spectre of mass lay-offs looms large. More than 110 power plants have shut since August, with operators citing lack of demand, while at least six major automobile plants have been forced to halt production due to low sales.

Investor sentiment is grim. Credit growth is falling and business confidence is at a six-year low.

So far, the government’s steps to address the problems have been far from reassuring. It has rolled back key tax proposals – such as a surcharge on foreign and domestic portfolio investors and a tax on start-ups – after criticism and has been mocked for the explanations it has offered for the slowdown, such as when Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman blamed poor car sales on millennials using Uber rather than buying their own vehicles.

India’s Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has been mocked for blaming poor car sales on millennials using Uber rather than buying their own vehicles. Photo: AFP

Economist and author Vivek Kaul says the government inaction is worrying. “The first step towards solving the problem is to accept it. Sadly, there has been no acceptance by the government that the economy is flailing, despite there being clear signs of a slowdown.”

One of the fundamental problems, Kaul says, is the lack of investment, a factor that may in part be caused by a lack of credible data regarding key economic indicators. On various occasions, the Modi government has discredited its own data when it showed unpleasant facts. In February this year, it junked its own report showing unemployment was at 6 per cent, a 45-year high, and rising, while last week, it distanced itself from another government report that showed rural consumption at a four-decade low.

How a wave of Chinese money is powering Indian start-ups

“These things don’t augur well for the country’s investor-friendliness,” says Kaul. “Credible data is important [to] foreign investors.”

‘THE CLEAN-UP’

The Indian government says it is engaged in a “clean-up” of the economy. In cracking down on a mounting pile of bad loans, it is pursuing the heads of some private banks and seeking the extradition of former employees who have caused massive losses before leaving the country.

But the clean-up has also meant India’s banking sector has taken a tumble. Banks have registered huge losses and major names such as the Punjab Maharashtra Cooperative Bank have gone bust. Others are on the verge of collapse. As a result, credit flows have come to a grinding stop.

Indians demonstrate against Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s demonetisation drive. Photo: AFP

Modi came to power in 2014 on the mandate of providing a “corruption-free” and “decisive” government that promised to act against economic offenders. However, this doctrine also drove it to demonetise 86 per cent of India’s cash in circulation in 2016, a step that proved disastrous for the economy, leading to 5 million job losses and an estimated 2 per cent drop in economic growth.

Still, even critics accept it is not all Modi’s fault. “Much of this mess has been inherited from the previous Singh-led coalition government. Action against [bank sector] offenders was necessary and welcome,” says Sucheta Dalal, the managing editor of Moneylife magazine.

What the government is guilty of, says Dalal, is conflating its clean-up with what she and many others call “tax terrorism”. She recalls various taxpayers seeking help who are being pursued over tax matters they thought had been settled up to a decade ago.

“The problem is, the government treats all of us as criminals and tax offenders. This criminalisation is particularly bad and expensive to deal with for smaller businesses and industries because of the hefty legal costs,” Dalal says.

Indian labourers carry clay bricks to a kiln in Farakka. The construction industry is among India’s biggest employers. Photo: AFP

(UN) EASE OF DOING BUSINESS

The effects can be devastating. In July, VG Siddhartha, a celebrated businessman who founded the Cafe Coffee Day chain, jumped into a river outside Bangalore. In his suicide note, Siddhartha blamed harassment by tax officials.

Various media commentators blamed the death on Modi’s government for “harassment” and “terrorism” on tax matters. Other, similar, cases have been reported and many more do not come to the public’s attention as many victims are too scared to speak out.

Making matters worse is the corruption that still permeates all levels of society. While the government claims to have cracked down on the problem – and India this year jumped 14 places in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business ratings to finish at 63 – the truth is that running a business remains a costly affair, largely due to the bribes that must be paid to government officials.

Nowhere is this clearer than in Mumbai, where the city government has said businesses can apply for licences online so as to leave no scope for corruption by officials.

What happened to India’s disappearing Chinese migrants?

“But officials told us that if we apply online, our permissions will be delayed by many months. The same officials are, however, happy to issue us the permits if we pay a bribe,” says one businessman trying to set up a restaurant.

That leaves the government with another problem: deciding whether to prioritise efforts to boost growth or clamp down on corruption.

“The government must realise that while the clean-up is good, it is far more important for it to improve the economy. There has been a complete failure of the administration in managing financial policy and that needs to be corrected immediately,” Dalal says.

Otherwise, critics warn, mounting unemployment could turn a financial tragedy into a human one. ■