Dr. Manoj Kumar Mishra, 12 October 2019

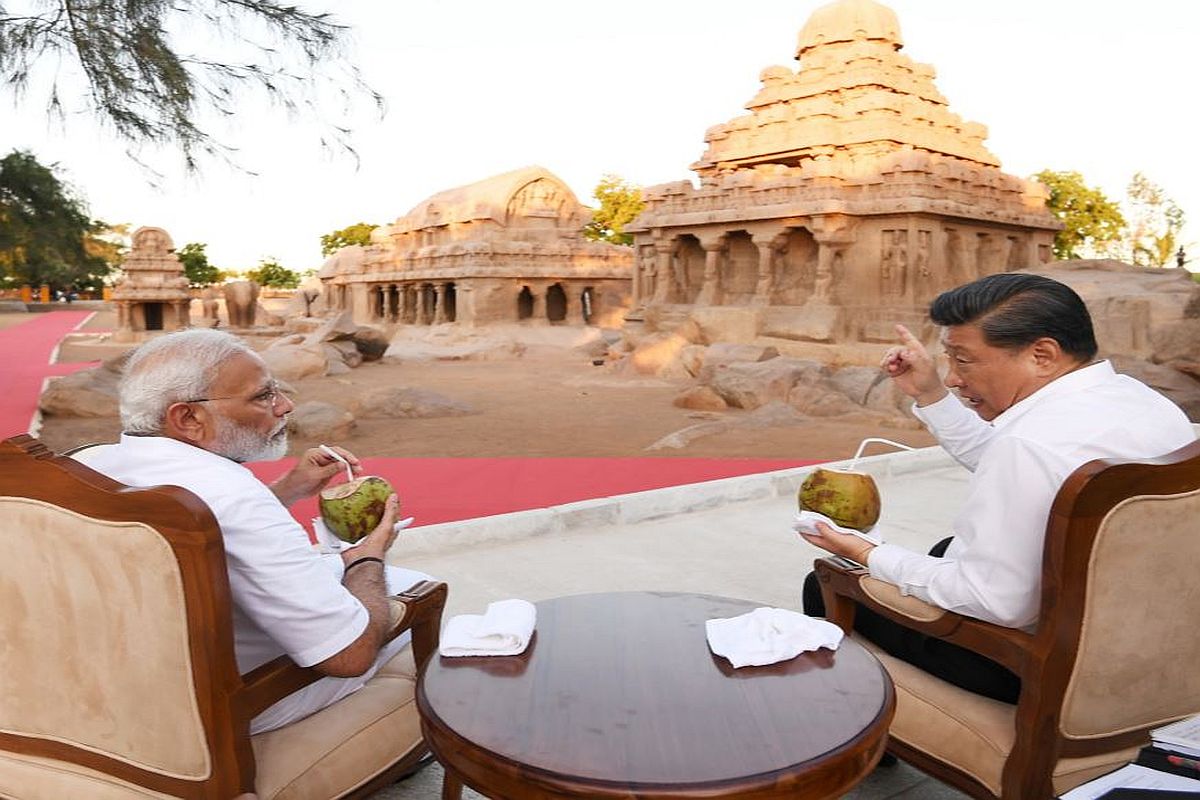

While the second informal meeting between India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping takes place at Mamallapuram, in the Indian city of Chennai after the two leaders met last time in China’s Wuhan in April last year, some attempts need to be considered in order to make the bilateral relationship more stable which is, in turn, contingent on a stable and peaceful continent across which both countries are primarily concentrating at expanding their influence.

India and China, two economic power houses of Asia are not only the key drivers of the economic renaissance that Asia is undergoing in the global economy but central to redefining the global economic order and heralding the Asian Century as well. However, the Asian Century, in real terms, and to be sustainable not only needs continued economic surge of the countries of the continent; it needs continuous attempts at developing some level of shared understanding in realms of regional peace, security and development which would not only contribute to sustain the rise of these two Asian powers but that could benefit other countries in the continent as well. While a study commissioned by the Asian Development Bank, Asia 2050: Realizing the Asian Century projected that Asian countries will keep growing and eventually account for more than half of global GDP by 2050, it did not, however, dwell on the factors that would sustain the economic stability of these countries. Some level of shared understanding on the notions of peace, security and development would also keep the hegemonic influences of external powers at bay. It is necessary that attempts at engendering some sense of common understanding in the realms of geopolitics, conventional and non-conventional threats and regional integration are undertaken. In this context, it is pertinent that two big powers of the continent maintain multidimensional relationships and work on shared perceptions on peace, security and development. It is worth mentioning that India’s former Prime Minister of India, Atal Bihari Vajpayee emphasized: “The 21st century will become the Century of Asia if China and India can build a stable and lasting relationship.” Ashok Kantha, Director of the Delhi-based Institute of Chinese Studies, is of the view: “it is debatable if the world could really enter an Asian age or an Asian century without the joint efforts of China and India, the two countries with the largest population and a mission to maintain peace and stability in the region and achieve its prosperity and rejuvenation”. However, India and China carried divergent views on the issues of peace, security as well as development which made the bilateral cooperation sporadic and fleeting.

The Asian Century would be meaningful if engagements within the continent are extensive as well as intensive enough to keep external hegemonic influences at bay. India and China share a common interest in the rise of a multi-polar world order and democratization of international trade and financial system, as well as the global energy market. Toward this objective, the two countries demonstrated their ability to pull resources together and helped establish Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), where India became the second largest investor after China. Assumably, they share common interests in strengthening cooperation under the frameworks of BRICS, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and the G20 as well. India and China also need to engage with each other and with other willing partner nations, particularly in the East Asia and the Pacific region in order to dent hegemonic geopolitical influence of external actors. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) could be a forum to realize this objective. Similarly, both countries need to cooperate in South and Southeast Asian region through regional and sub-regional cooperation.

Geopolitics defines conflicting perspectives on peace, security and development

However, perceptual divergences on regional security and development issues have pushed both countries into irreconcilable positions such as India’s unwillingness to facilitate China’s membership in the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and China’s reluctance to strengthen the Bangladesh China India Myanmar (BCIM) sub-regional initiative. While references to explore ‘China-India Plus one’ or ‘China-India Plus X’ cooperation to achieve mutual benefits and win-win outcomes between China and India were very often resorted to, no substantive headway was made in this direction. For instance, cooperation on Afghanistan was agreed upon when the leaders of India and China met in Wuhan in April last year. Similarly, both shared similar views on climate issues and cooperated in some instances to secure energy supplies. US-China trade war also induced India-China cooperation in specific areas of trade besides existing trade of multi-billion rupees. However, India-China cooperation has been occasional, fleeting and issue-specific and both differ in their perceptions on geopolitical objectives as well as means to attain these. Both also carried varied perceptions on threat as well.

While the Chinese President Xi Jinping carried a vision to see his country playing a larger role in global affairs which was evident in his announcement to turn China into a leading nation in terms of national power and global impact by 2050 at the 19th National Congress of the Communist party in October 2017, his unflinching focus on the implementation of the Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI) pointed to his country’s strides toward this direction. However, many of Indian strategic thinkers and policy makers argue that geostrategic designs underlying the BRI are clearly discernible. Flipside of the ‘BRI’ that was encountered by some of the Asian countries like Malaysia, Sri Lanka and Myanmar also contributed to Indian concerns that the mega project raises more speculations and inspires less trust as to the claim that it is purely a commercial venture without strategic designs.. Specifically, the act of Sirisena government of Sri Lanka leasing out Hambantota port to China for 99 years under debt pressure, corroborated the Indian contention that the ‘BRI’ is not merely an infrastructural and connectivity project rather loaded with military and strategic objectives. Referring to India’s security concerns in its strategic periphery, some of India’s strategic experts argue that the “BRI is primarily South Asia and IOR centric, as is evident from the number of projects in these regions – CPEC, CMEC (China-Myanmar Economic Corridor), ‘Nepal-China Trans Himalayan Multi-Dimensional Connectivity Network’ including Nepal-China cross border railway, besides significant projects in Bangladesh, Maldives and Sri Lanka. The Maritime Silk Route encompasses major ports such as Kyakhphu in the Bay of Bengal and Gwadar in the Arabian Sea. On completion of the above ventures, China will enjoy a competitive edge in the region”. Some experts on strategic affairs preferred to argue while New Delhi believed: “connectivity in Asia must be consultative, and guided by transparent financial guidelines, principles of good governance, internationally recognized environmental and labor standards, and respect for sovereignty. China, on the other hand, is intent on shaping a unipolar Asian order that will be defined by deference to the Middle Kingdom and its increasingly imperial rulers”.

Apart from stressing on the need for rule-based transparent financial engagements under the BRI, India has expressed its specific concerns as regards the mega project’s violation of sovereignty and territorial integrity particularly with reference to inclusion of Gilgit-Baltistan region into the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project which India considers as its integral part. Juxtaposing China’s BRI and India’s efforts at creating overseas infrastructure, Indian foreign minister S. Jaishankar is reported to have remarked that India believed in a ‘softer and collaborative diplomacy’ and India’s ways of executing projects stem more from a sense of partnership rather than an “all mine” attitude. He said: “The manner in which we do things is more aggregated and more organic”.

However, some Indian experts representing a miniscule body of analysts underline the overall popularity and success of the BRI and suggest New Delhi to reconsider its stance. They also argue that the long-term success of the BRI also needs India’s support to the mega project. The demographic factor that China’s population of working age is projected to shrink by 200 million people by 2050 while in India the working-age population would increase by 200 million is considered one of the reasons why India as a source of influence, investment and market must be key to the regional exercise of connectivity and infrastructure-building in the long-term. They argue that the BRI “is evolving towards standards of multilateralism, including through linkages with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The International Monetary Fund describes it as a “very important contribution” to the global economy and is “in very close collaboration with the Chinese authorities on sharing the best international practices, especially regarding fiscal sustainability and capacity building”.

While unresolved territorial claims since India’s independence shaped bilateral perceptions on peace, security and development, recent Doklam standoff in the high Himalayas pointed to the continuing trust-deficit between the two countries as well as it raised a geopolitical question as to how both could reconcile their positions in ‘overlapping peripheries’. China’s increasing arms supplies to some of India’s neighbours, heavy infrastructure building exercise in its neighborhood such as ports, railways, airports and interconnecting roads under the BRI corroborated the perception that the former was incessantly engaged in multiplying its influence in what the latter considers its strategic periphery.

India’s commitment to a strategic partnership with the US on the one hand and attempts at forging bilateral ties with China on the other also did not convince China that the strategic partnership was not directed at undercutting Beijing’s geopolitical influence. In this context, it has been argued: “China would be more flexible in dealing with India if it is convinced of India’s equidistance with the U.S. on China-U.S. disputes involving distant places such as Taiwan and South China Sea islands”. India-China relations cannot truly herald the Asian Century until they make sincere attempts at engendering some level of understanding on regional peace, security and development.