August 15, 2018

Today, the Taliban continue to fight government forces in Afghanistan, recently launching major attacks such as those in Ghazni and demonstrating the persistence of the challenges at hand. But recall that after the Taliban government was ousted in 2001, Afghanistan made great strides towards democratization, rebuilding its political system around democratic institutions and norms such as universal suffrage and freedom of speech. Political participation increased significantly, which was not possible during the Taliban regime, particularly among Afghan women (in the last parliamentary election, women were elected for 27% of the seats, meeting the minimum requirements set out in the 2002 Afghan constitution). National elections allowed citizens to choose their leaders in a peaceful transition of power. Other significant strides included the adoption of a new constitution and the growth of a free and vibrant media and a committed civil society.

Yet, nearly 17 years later, declining public support for democracy and its key institutions has placed these achievements at risk. As documented in The Asia Foundation’s annual Survey of the Afghan People, the proportions of Afghans who are satisfied with democracy, have confidence in the Independent Election Commission (IEC), trust their members of parliament (MPs), and feel safe participating in public political activities are all in significant decline.

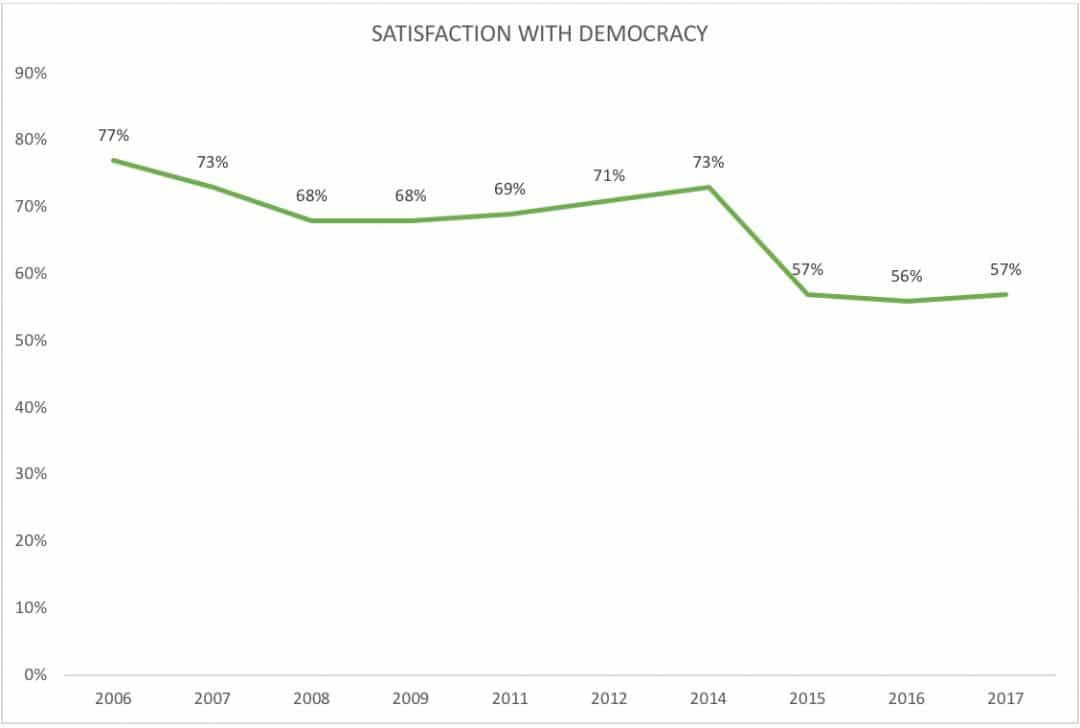

In 2006, when the Survey first asked the question, 77% of Afghans indicated that they were satisfied with democracy. In 2017, this number had fallen 20 points, to just 57% (figure 1), after a decade that included widespread allegations of fraud in the 2014 elections and months of ensuing political gridlock, verging on civil war, that was only resolved when U.S. secretary of state John Kerry persuaded the rival candidates to form a national unity government and submit to a recount.

FIG. 1: Q-44. On the whole, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with the way democracy works in Afghanistan? By democracy, we mean choosing the president and parliament by voting, rather than appointment or selection by some leaders. (Percent who responded “very” or “somewhat” satisfied.)

In an emerging, postconflict democracy, a trusted, independent election commission is a key institution underpinning the legitimacy of elections. In Afghanistan, however, public confidence in the IEC has been declining. The IEC failed to hold scheduled parliamentary elections in 2015, postponing them first to July 2018 and now to October. Government officials have repeatedly been accused of interfering with the work of the IEC. The head of the IEC recently claimed that interference by police chiefs and civilian officials was hindering the candidate registration process, and the deputy head of the IEC has accused President Ashraf Ghani of meddling in the IEC’s affairs. In 2014, when Afghanistan last held national elections, the Survey found that 66% of Afghans had confidence in the IEC. In 2017, that confidence had declined significantly, to 38% (figure 2).

FIG. 2: Q-51c. Do you have a lot, some, not much, or no confidence at all in the Independent Election Commission? (Percent who responded “a lot of confidence” or “some confidence.”)

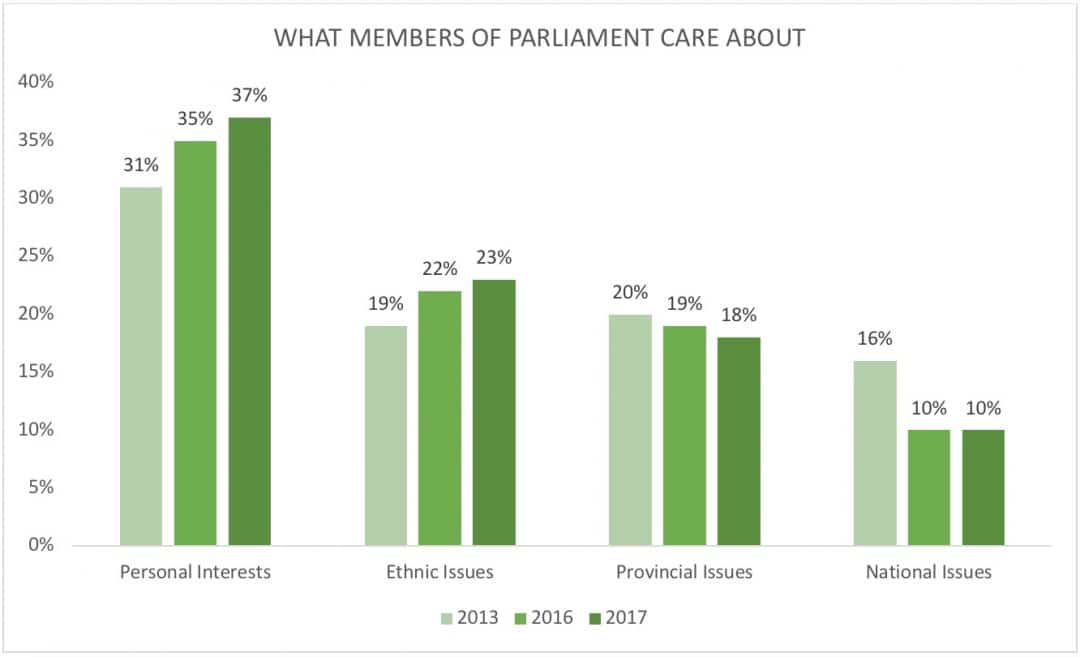

In democratic societies, parliaments are tasked with conducting oversight of government performance and promoting good governance. But Afghanistan’s parliament has itself been tarnished by allegations of corruption. An Afghan media investigation in 2017 accused the speaker of parliament and the chief secretary of embezzling thousands of dollars. In another case, MPs in the lower house accused the first deputy speaker and another MP of forcibly removing documents from the National Archive. The Survey has found that Afghans have increasingly negative views of their MPs. In 2013, 16% of respondents said their MPs cared about national issues, while 31% said their MPs cared only about their personal interests. In 2017, only 10% of respondents said their MPs cared about national issues and 37% said they cared only about their personal interests (figure 3). Just 35% were confident that their MPs were doing their job, a 12-point decline since 2013.

FIG. 3: Q-49. In your opinion, which of the following does your member of parliament care about most: national issues, provincial issues, district or municipality issues, ethnic issues, or personal interests?

Freedom of speech, political participation, and the right to criticize the government are fundamental rights of citizens in a democracy, and they are among Afghanistan’s principal democratic gains since 2001. But deadly attacks on political gatherings and peaceful demonstrations are undermining these freedoms. In July 2016, for example, the Islamic State claimed responsibility for twin suicide bombings that killed 80 and wounded 230 at a peaceful political march in the capital city of Kabul. Survey data shows a concomitant rise in fear of participating in civic activities among Afghans. In 2006, 61% of respondents expressed fear of participating in a peaceful, public demonstration. In 2017, this number had risen to 72%. In the capital, where most political gatherings occur, fear of public participation rose 20 percentage points, from 61% in 2016 to 81% in 2017 (figure 4).

FIG. 4: Q-45. Please tell me how you would respond to the following activities or groups. Would you respond with no fear, some fear, or a lot of fear? (b) Participating in a peaceful demonstration. (Percent who respond “a lot of fear” or “some fear.”)

As the October elections approach, insurgents have launched deadly attacks on voter registration centers in Kabul, Nangarhar, Ghor, and elsewhere. A suicide attack on April 22, 2018, in a Shiite-dominated neighborhood of Kabul killed 50 and wounded 120 innocent civilians who were queuing to receive their voter identity cards. Hundreds of voter registration centers failed to open in provinces like Balkh, Jawzjan, and Kunduz, and the IEC announced in late May that 461 out of 4,491 voter registration centers nationwide are in areas under Taliban control. According to U.S. government data, the Afghan government controls just 56% of the country’s 407 districts; 30% are contested; and 14% are under insurgent control.

Widespread allegations of fraud in the 2014 presidential election significantly reduced Afghans’ confidence in the electoral process and the value of their votes. Delayed elections and charges of political interference have undermined the credibility of the IEC. Allegations of corruption have increased the public’s mistrust of parliament. Insurgent attacks have thwarted voter registration in many areas and made Afghan citizens fearful of public participation in the political process. October’s long-delayed elections will be a crucial test of the state of democracy in Afghanistan. Their success is far from assured.

Mohammed Shoaib Haidary is a program officer for The Asia Foundation in Afghanistan. He can be reached at mohammadshoaib.haidary@asiafoundation.org The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and not those of The Asia Foundation.