September 30, 2020 Asia Foundation

Nepal is an extremely diverse country, with 126 castes and ethnicities and many cultural, religious, and linguistic groups and subgroups. The number of languages spoken in Nepal is still uncertain. The 2011 census recorded 123 distinct languages, but several more were subsequently discovered, and the true number may be as high as 200.

Despite this linguistic diversity, the official Nepali language (Khas Bhasa) has dominated the printed word, along with some English. The 1990 People’s Movement began a slow revival of writing in Nepal’s many other languages. The ethnic political movements of the 2000s included the recognition and protection of mother tongues among their demands, and the 2015 Constitution does enshrine some rights for minority languages, but it is still very difficult for Nepali children of indigenous and minority ethnicities to find reading opportunities in their native languages.

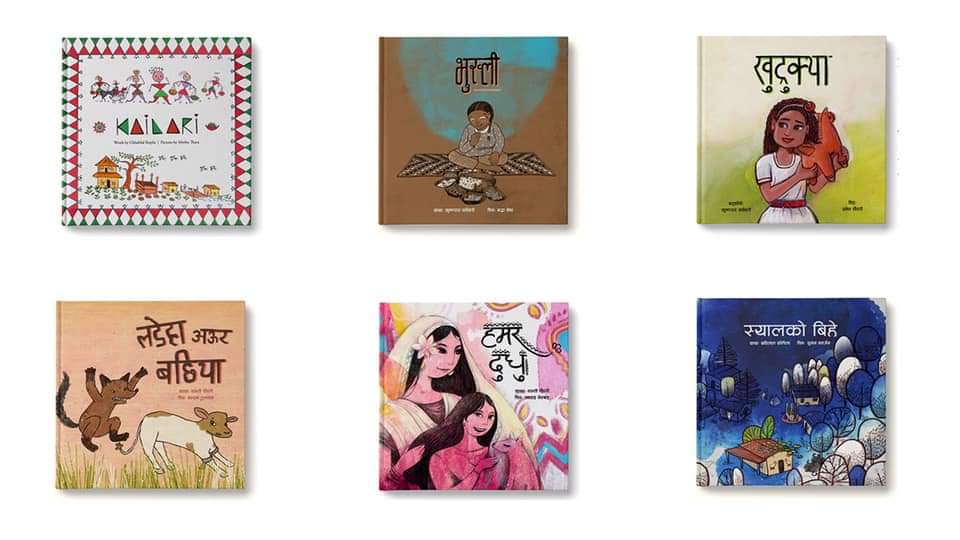

In 2019, The Asia Foundation’s Let’s Read Nepal and a creative team of local authors, illustrators, and arts advocates published six new books for children in Tharu, one of the indigenous languages widely spoken in the southern plains of Nepal known as the Terai. The Tharus themselves have a long history as bonded laborers, or Kamaiyas, in the service of other groups. Though they were officially emancipated in 2000, many Kamaiyas, who were often released into a state of landlessness and poverty, have yet to receive real relief or rehabilitation from the government.

Last year, Let’s Read Nepal published six new illustrated books for children in the minority Tharu language.

Hamar Dudhu

Author and poet Shanti Chaudhary is a member of the Tharu community. Her story Hamar Dudhu (My Mother) is written in the form of a song remembering her mother and honoring her strength and her ability to speak with her own voice, though she had no education. The song celebrates Dudhu as a kind and loving mother who wove beautiful baskets, or mouni.

My Dudhu is always with me.

She wove the most beautiful mouni,

And left an entire legacy.

The story offers many glimpses of Tharu customs, traditions, and troubles. In one passage, Shanti writes how her mother quietly rebelled against her husband’s patriarchal violence.

Once, when Buwa hit Dudhu,

The glass bangles on her wrist broke.

She never wore them again.

So, when Buwa passed away,

My Dudhu had no bangles to break.

My Dudhu was fierce and strong.

She said, “Never tolerate what’s wrong.”

In Hamar Dudhu, illustrated by Ubahang Nembang, author Saraswati Chaudhary tells the story, in the Tharu language, of her mother’s life.

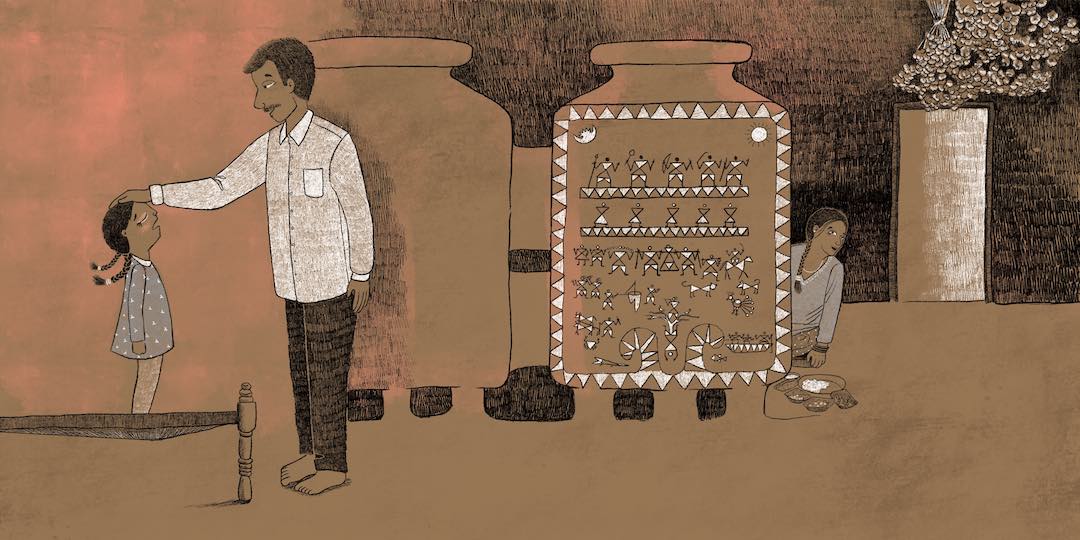

Bhukkali

Bhukkali, written by Krishnaraj Sarbahari and illustrated by Shraddha Shrestha, is set in the recent past, when Baburam Bhattarai, the prime minister of Nepal, visited many of the camps of emancipated Kamaiyas. The story is reminiscent of the struggle to create the new constitution, a time in which long-marginalized groups began to reassert their cultural and political identities. It can also be seen as a metaphor showing that Tharus can be strong even if the state does not fulfill their expectations.

In the story, Bhukkali, a Tharu girl, is expecting the prime minister to give her a chocolate when he visits her home. But he does not, and she is hurt. Her father consoles her, telling her, “Don’t cry, chhori [daughter], he has promised to make our village bright and colorful.” Replies Bhukkali, “He couldn’t even carry a small piece of candy.… I can make our village bright and colorful on my own! I don’t need his help.”

Bhukkali, written by Krishnaraj Sarbahari and illustrated by Shraddha Shrestha, is set in the recent past, when Baburam Bhattarai, the prime minister of Nepal, visited the camps of emancipated Kamaiyas

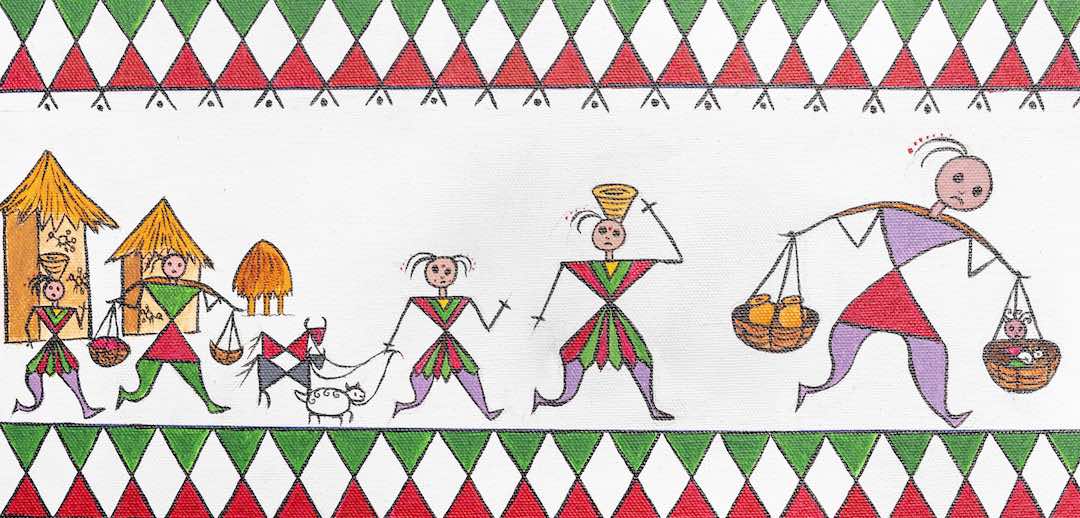

Kailari

Kailari, by Chhabilal Kopila, is a tale, drawn from true events, about the journey of Dangaura Tharu families who left the Dang district in the Terai to settle in the town of Kailari. The beautiful illustrations by Mitthu Tharu won the Lalit Kala Bishesh Puraskar award from the Nepal Academy of Fine Arts. They are in the Astimki style, traditionally painted with homemade paints in the interiors of Dangaura longhouses during the Tharu festival of Krishnastami, which celebrates the birth of Lord Krishna.

Kailari, by Chhabilal Kopila recounts the journey of Dangaura Tharu families who left the Terai to settle in the town of Kailari. The beautiful illustrations, in the traditional Astimki style, are by Mitthu Tharu.

Let’s Read Nepal first launched its series of minority-language children’s books in 2018, with six stories in Nepal Bhasa, the language of the Newars, the indigenous people of the Kathmandu Valley. Once the nation’s official administrative language, Nepal Bhasa has a long oral and written tradition, but from the early 20th century until the country’s recent democratization, Newar was suppressed, and today Newar speakers are attempting to revive the language.

The Great Hairy Khyaa

The Newar stories were adapted from six children’s songs by the famous poet Durga Lal Shrestha, often honored as Janakabi (People’s Poet). Shrestha’s songs have become widely known throughout the Kathmandu Valley, and collections of his children’s songs have been through multiple editions and are still circulating today. In the sing-along book Dhapla Khyak (The Great Hairy Khyaa), Durga Lal Shrestha revives the tale of the khyaa, a monster who comes to life in the dark. The original children’s song, first released on CD more than 30 years ago, tells the story of a child’s fear of the dark.

No! I am scared to go where it’s dark.

Ma, is this the khyaa that scares me so?

By the end of the book, the children have learned that the khyaa, who lurks in the dark house at night, disappears when the light is turned on. They sing:

What kind of khyaa is afraid of light?

But what about me, who’s such an easy bite?

The Great Hairy Khyaa is a classic children’s tale of the Newar people about monsters in the dark. It’s retold in the Nepal Bhasa language by the famous poet Durga Lal Shrestha, with illustrations by Suman Maharjan.

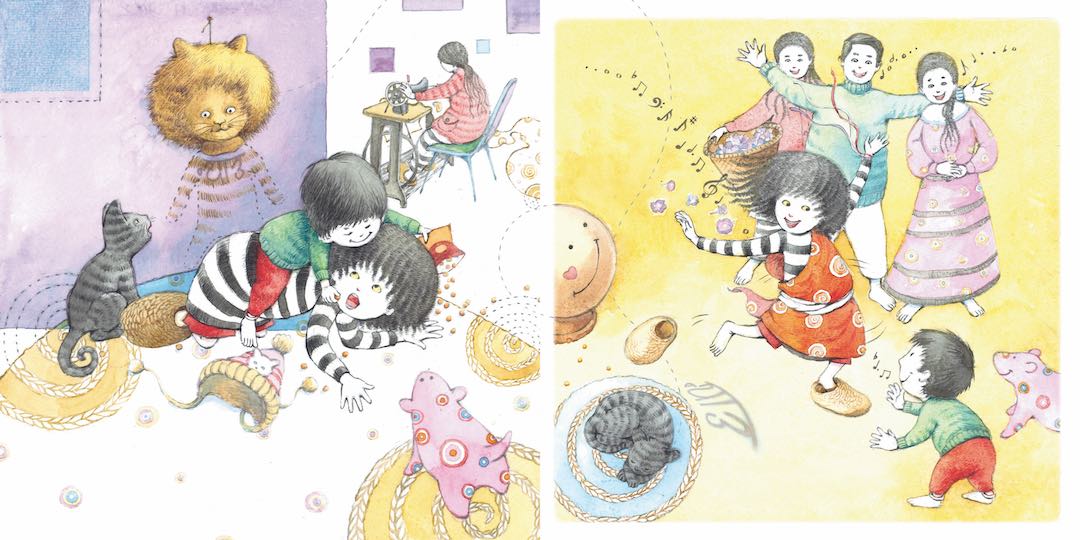

Meow Meow

Meow Meow is a story full of childhood innocence and the simple moments of daily life. This tale of a girl befriending a cat who visits her house was a popular children’s song on the radio until a generation ago. The setting is a Newari household, but the story speaks to everyone about the day-to-day experiences that we sometimes forget to savor.

When Ma has lots of work,

we watch over little brother.

Skipping, jumping, dancing,

we laugh with one another.

Meow Meow, by Durga Lal Shrestha, with illustrations by Surendra Maharjan

These stories from two of Nepal’s indigenous groups give just a hint of the wealth of history and folklore with which minority cultures here abound. Sharing them with rest of the country and the world is a way of celebrating the diversity that exists within Nepal’s 147,181 square kilometers, while cultivating a love of reading among the nation’s youth.

In addition to Newari and Dangaura Tharu, Let’s Read Nepal has translated children’s stories into Nepal Bhasa, Bara Jilla Tharu, Rana Tharu, Tamang, and Limbu. A recent Let’s Read BookLab focused on folktales from across Nepal. They can all be found in the Let’s Read online library, where they are also available in English. Let’s Read is proud to publish these books for children in their mother tongue, and to bring these stories from many cultures to English-speaking children as well. We hope our InAsia readers will join their children in enjoying these stories from Nepal.

My Dudhu and other Tharu stories can also be enjoyed as audiobooks on YouTube

Shreya Paudel is a program officer in The Asia Foundation’s subnational governance program, Shameera Shrestha is an officer with Books for Asia, and Ritica Lacoul is senior program manager for Books for Asia. They can be reached at shreya.paudel@asiafoundation.org, shameera.shrestha@asiafoundation.org, and ritica.lacoul@asiafoundation.org, respectively. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors, not those of The Asia Foundation.